Posting Houses

Garstang was an important location for Britain's road transport network, as it provided fresh horses, fodder, beds, and provisions for coaches passing through.

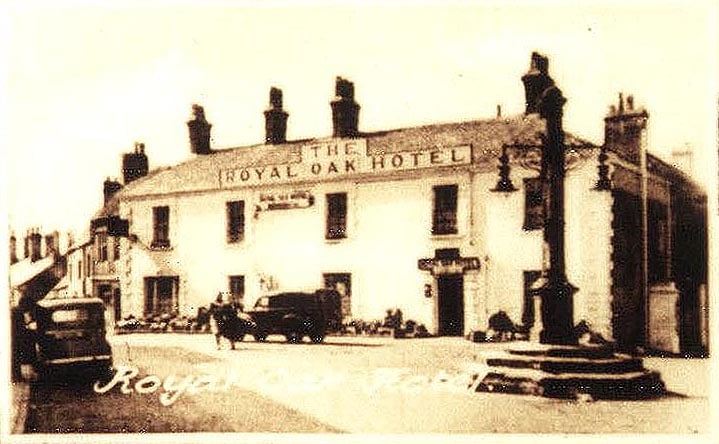

The Royal Oak Hotel was Garstang’s principal Posting House on the London to Edinburgh route. Weary travellers could put their horses in the stables and get a bed for the night.

Sir Walter Scott (famous 19th century Scottish author, poet, and historian) and Celia Fiennes (17th century travel writer who toured England on horseback - very unusal for a woman at the time!) are amongst some of the famous people that have stayed there. The block of buildings on the west side was used by Cromwell’s troops during the siege of Greenhalgh Castle.

The Royal Oak owned much land stretching to beyond St. Thomas’ Church and right down to the river. It was used for many community gatherings.

At the right hand corner of the Royal Oak Hotel note the marks on the cornerstone where the old coach wheels caught the stonework!

Stage Coaches - Life in the fast lane (at 12 mph)!

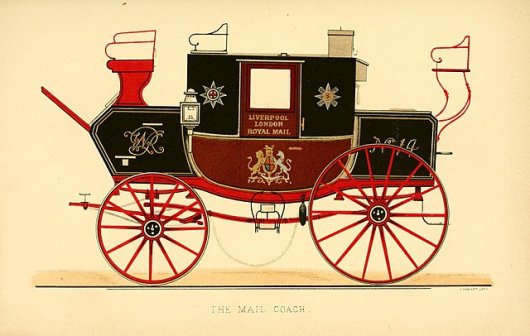

There were stageposts or posting houses all along the main travel routes, usually about ten to fifteen miles apart, where the stage coaches stopped to change horses and passengers could stretch their legs and perhaps get some refreshment. When night fell, normal stage coaches stopped, but were away at first light the next day. "Express" coaches travelled through the night.

By the 1750s better roads and coach design had cut the travel time from Manchester to London substantially:

"However incredible it may appear, this coach will actually (barring accidents) arrive in London in four days and a half after leaving Manchester" (Advertisement for the Manchester 'Flying Coach")

The stage coaches ran on set routes at set times, and were quite expensive, but also provided a way to send packages to relatives. The coaching companies allowed the coachman to accept and deliver items along the route, as long as it didn't interfere with the journey or take up too much space in the 'basket' used to store passenger luggage.

If you were wealthy, or needed to deliver something in a great hurry (such as news of national importance) you could hire a 'post chaise' which was a smaller and lighter private vehicle with room for only two passengers, and instead of a coachman had a postillion riding one of the horses. In 1805, the news of the Battle of Trafalgar was taken by "posting" from Falmouth to London in just 37 hours.

Travelling by stagecoach was uncomfortable, especially if you were doing it on the cheap as an "outside" passenger travelling on the roof. However, the extensive network of roads, inns and changing posts was much admired by visitors from other countries, and continued until replaced by the faster and more comfortable railway network.